Nature is the best artist, sculptor and designer. Her creations are amazing and perfect, they amaze with the selection of shades and filigree elaboration of the smallest details. Man always tried to repeat the best of her samples. Sometimes he does it well!

In the photo on the left – flowers of the perennial Aster Symphyotrichum, also called Novobelgian or Virginian. In the photo on the right – the same flowers, only… glass.

Glass jellyfish and flowers by Leopold and Rudolph Blaschke

Czech Leopold Blaschka came from a family of hereditary glassblowers who worked in Venetian and Bohemian glass workshops. “My grandfather was the most famous glassblower in the Czech Republic,” said Leopold Blaschka.

Drawing on his inherited craft and training in jewelry as a young man, Leopold Blaschka took up the production of jewelry and glass eyes for prosthetics and taxidermy.

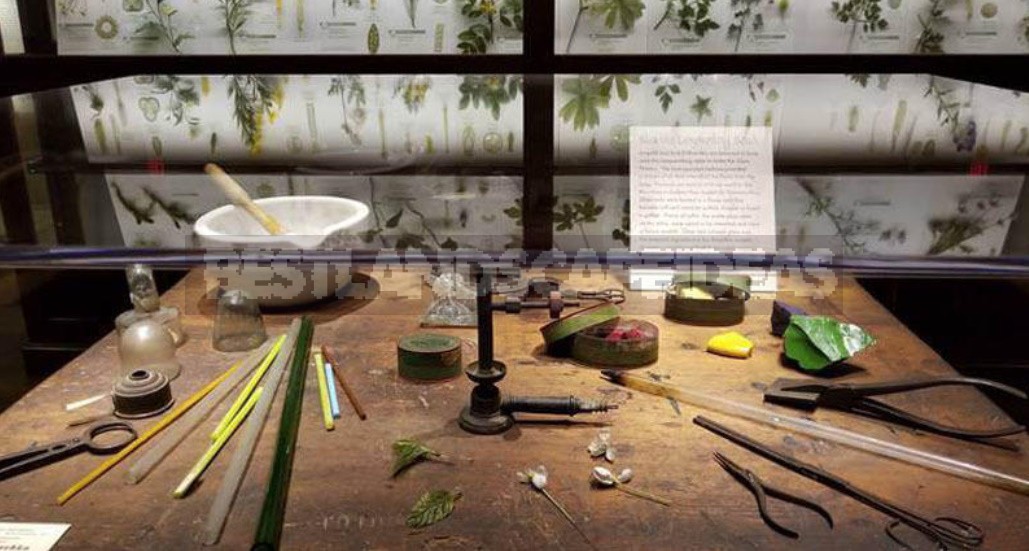

While doing business on his own, Leopold Blaschka developed a technology that allows you to make the smallest details out of glass. He called it “spinning glass.” Things were going well, but in 1850, his wife and son died of cholera, and some time later – and Leopold’s father. In his grief, he sought solace from nature, wandering around the neighborhood and making sketches of meadow plants.

Jellyfish and sea anemones

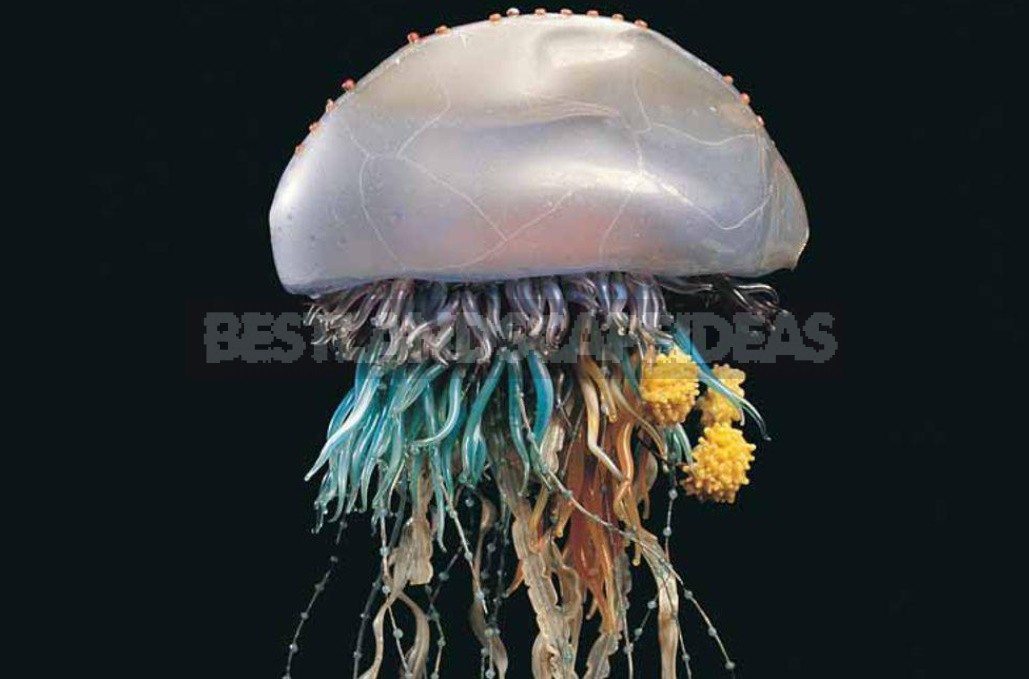

A couple of years later, Leopold Blaschka went on a trip to America. During the voyage, the glassblower observed an extravaganza of marine invertebrates – jellyfish, whose transparent bodies were so similar to Blashka’s favorite glass.

In his spare time, Leopold began to make crafts from colored glass – models of sea creatures he had seen and sketched. Thanks to their observation and attention to detail, the glass jellyfish were exact replicas of living prototypes.

Works made for fun were noticed: the naturalist and collector Prince Camille de Rohan ordered the master to make 100 glass orchids. A Professor at the University of Dresden, Ludwig Reichenbach, persuaded Leopold Blaschk to make a collection of sea anemones for the natural history Museum in Dresden.

Reichenbach insisted that Blaschka abandon his established business of producing haberdashery and products for pharmacists and medical professionals in favor of making naturalistic glass models for aquarists, collectors and museums.

Professor Reichenbach was right: Leopold Blaschke was a success. Unique glass models of plants, insects and marine animals have been popular with Museum workers around the world because of their skill and scientific accuracy. The glassblower moved to Dresden, and the master’s son from his second marriage, Rudolf, who was even more talented than his father, joined the business.

Glass flowers

George Lincoln Gooddale, Director of the Harvard Botanical Museum, suggested that the masters fulfill a large order – a Botanical collection to show to students. After initially refusing due to the workload of making glass models of sea creatures, Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka eventually signed the first contract for ten years. After that, the masters created a unique collection, all the exhibits of which, unlike the sea creatures sold in the catalog, were made in a single copy.

It was glass flowers for Harvard that brought the greatest fame to Czech master glassblowers. Over five decades of collaboration, 4,400 Botanical models belonging to 160 taxa have been created. Of these, 780 show plants in full size, there are also enlarged fragments, as well as details of flowers and fruits in the section.

To maintain scientific accuracy in the models, glassblowers studied plants from atlases, Museum collections, and Botanical gardens. Rudolph made several expeditions to different parts of the world, where he collected plant samples and made sketches. They even sowed and grew some plants to be able to work from nature.

In 1895, Leopold Blaschka died, and Rudolph continued to create models for Harvard. In particular, I made models of plants damaged by various diseases, and fruits in various degrees of rotting – do not forget that glass flowers were conceived primarily as a textbook for botany students.

Rudolph worked on a collection of glass flowers until the age of 80, when he announced his retirement. Father and son Blashka did not take students. Rudolph’s family was childless, so the skill and secrets of the glassblower family had no heirs.

Today, glass flowers are in the Museum of the Botanical garden of Harvard University and are the most popular exhibit, always striking the audience with the highest skill of execution.

Together with the figures of sea creatures, Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka created almost fifteen thousand glass models, the equal of which no one has managed to make to date. “An artistic miracle in the field of science and a scientific miracle in the field of art” – so they say about the work of artisans, artists and biologists Leopold and Rudolf Blaschk.